The editor holds a very special position in the filmmaking process. An artist in his own right, the editor is tasked with assembling the rough footage in a way that fulfills your vision. However, whereas you have been involved with the film for months, possibly years, the editor has an objective point of view and can spot problems in story and pacing you may never see. For this reason, you must trust the editor and give him breathing room to build the story.

As the director of your movie, you’ve been involved in virtually every step of the process – from writing the script to shooting the footage on set. But now that you’re in post-production, you have the opportunity to work with someone who can bring something to the project that you can’t – objectivity.

The challenge that somebody has to have, and most often that challenge is met by the editor, what is actually relevant to the telling of the story. They weren’t on set, they didn’t get up at five in the morning and fight the mosquitoes to get that incredible opening shot as the sun came up over the swamp and people were dying left and right because the bugs were thick and the air was hot and it was just a miserable [experience]; they don’t care, they want to tell the story.

– Larry Jordan, Award-winning post-production trainer, member of the Directors Guild of America and the Producers Guild of America

The biggest disservice you can do for the film is to sit over the editor’s shoulder and direct each edit. This common mistake not only takes away the editor’s creativity as an artist, but also your ability to make objective decisions as to how the film will cut together. Let’s face it, you have spent months, possibly years working on the movie and know every detail of the story. Subsequently, plot holes may be invisible to you as you mentally fill in gaps with your knowledge and familiarity with the story. That’s why working with an editor is so important – editors come onboard later in the process and aren’t exposed to the creative process during production. When they receive the footage, they can objectively build the story with the available shots.

One of the most difficult scenarios with a director, is one who is a little too controlling for their own good, because sometimes, directors, and it really comes from a state of passion, I find, they have their vision, and they’re so set on their ways that they can come into the editing room and completely dominate the process. And it’s a very uncomfortable position for an editor to be in because it doesn’t give the editor time to really explore the footage on their own and see if there are alternative ways to create the scenes.

– Brad Schwartz, Emmy-winning Editor, “Top Chef,” “Dancelife,” and “Viva Hollywood”

Be smart and give the editor guidance that allows him to build the assembly cut alone. Once the assembly cut is finished, can come in fresh, watch the film and give the editor notes as to what changes need to be made.

Some tips and tricks to keep in mind when working with an editor:

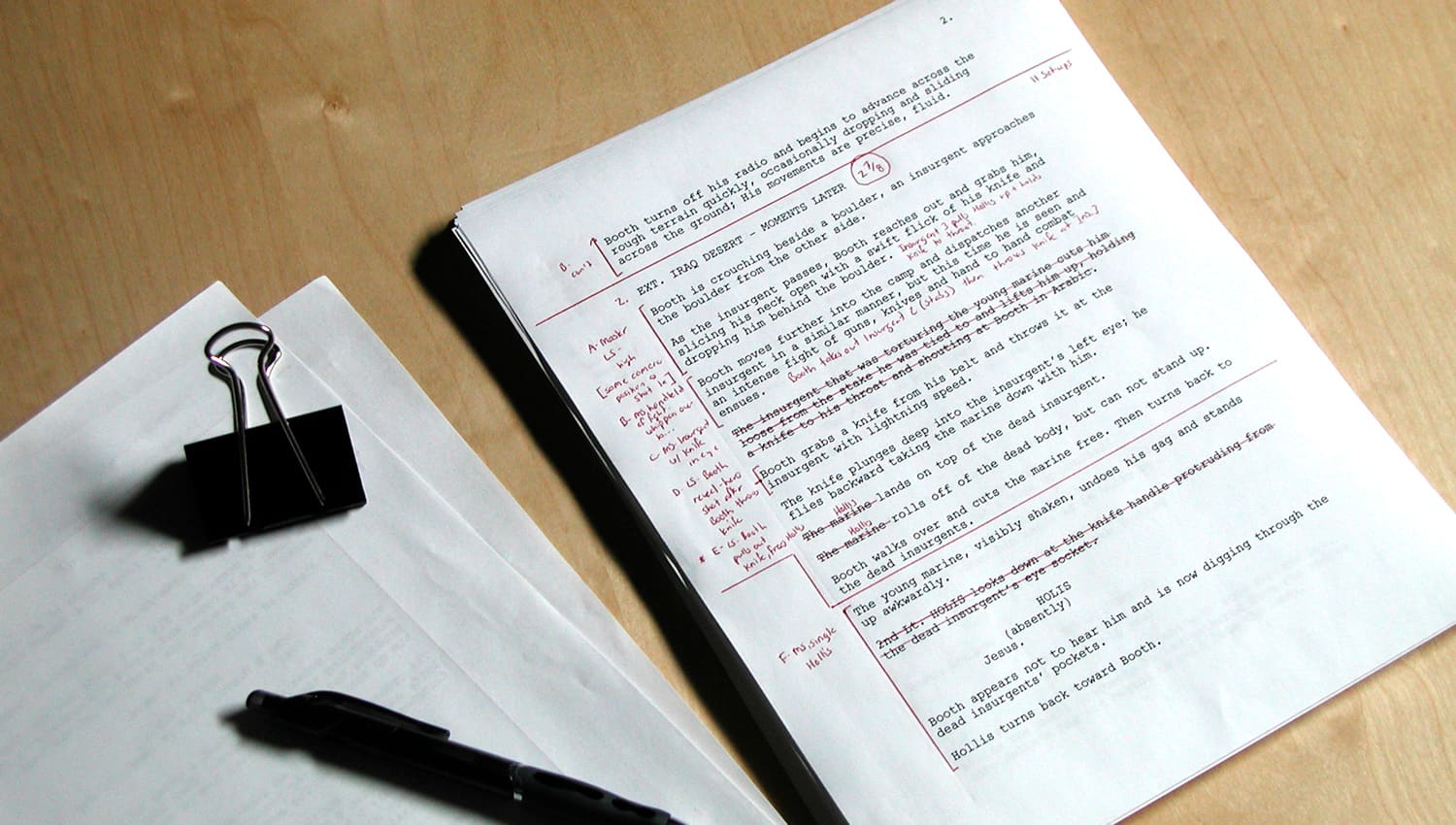

- Concentrate and focus – The editor is the keeper and manipulator of the footage, builder of the story and the objective eyes of the director. Tasked with building the best possible story out of potentially thousands of shots, sound effects, lines of dialogue and music cues, it’s important to be completely immersed in the story and footage. Part of being able to concentrate is setting up a quiet area where he can work uninterrupted. Make sure the editor can aside specific time to work on the film, turning of the phone or television so he can fully immerse himself in the world you are creating. Although it takes hundreds of people to produce the footage, it really rests on the shoulders of the one editor to put it together.

- A good editor spends more time thinking than editing – The actual physical process of cutting a film is fairly quick and easy; but the majority of the editor’s time is spent discussing the ordering of scenes, what shots work and which don’t, options and alternate ways of telling the story, how to improve the performances, how to correct pacing issues, and address the flow of the story. The editing process involves a little bit of cutting, but a lot of thought, discussion and analyzing to determine whether the edit has improved the movie. Welcome, and be open to, this dialogue, for it is in these conversations that the real art of editing happens.

- If you’re directing the movie, bring on an experienced, objective editor – No matter how good of an editor you think you are, NEVER cut your own film. You know it too well and will mentally fill in plot holes because you know the story so well. You need the objectivity of a third party.

Ultimately, a good editor needs time to wrap his head around the material to find the best way to assemble the story. Trust him, and let him have a pass at the material before you jump in. You may just be surprised at the result.