Although we all think of the director as exerting his or her influential on set, in reality the director’s work is mostly done well before hand in pre-production. It’s easy to get overwhelmed by the complexities of production. From working with difficult actors, to fighting the setting sun, to trying to overcome problems with the location, it’s easy to lose sight of the fragility of the emotional moment you’re tasked with creating amid this chaos. As a result, it’s always best to do your homework in a quiet environment, and look to your script for the answers.

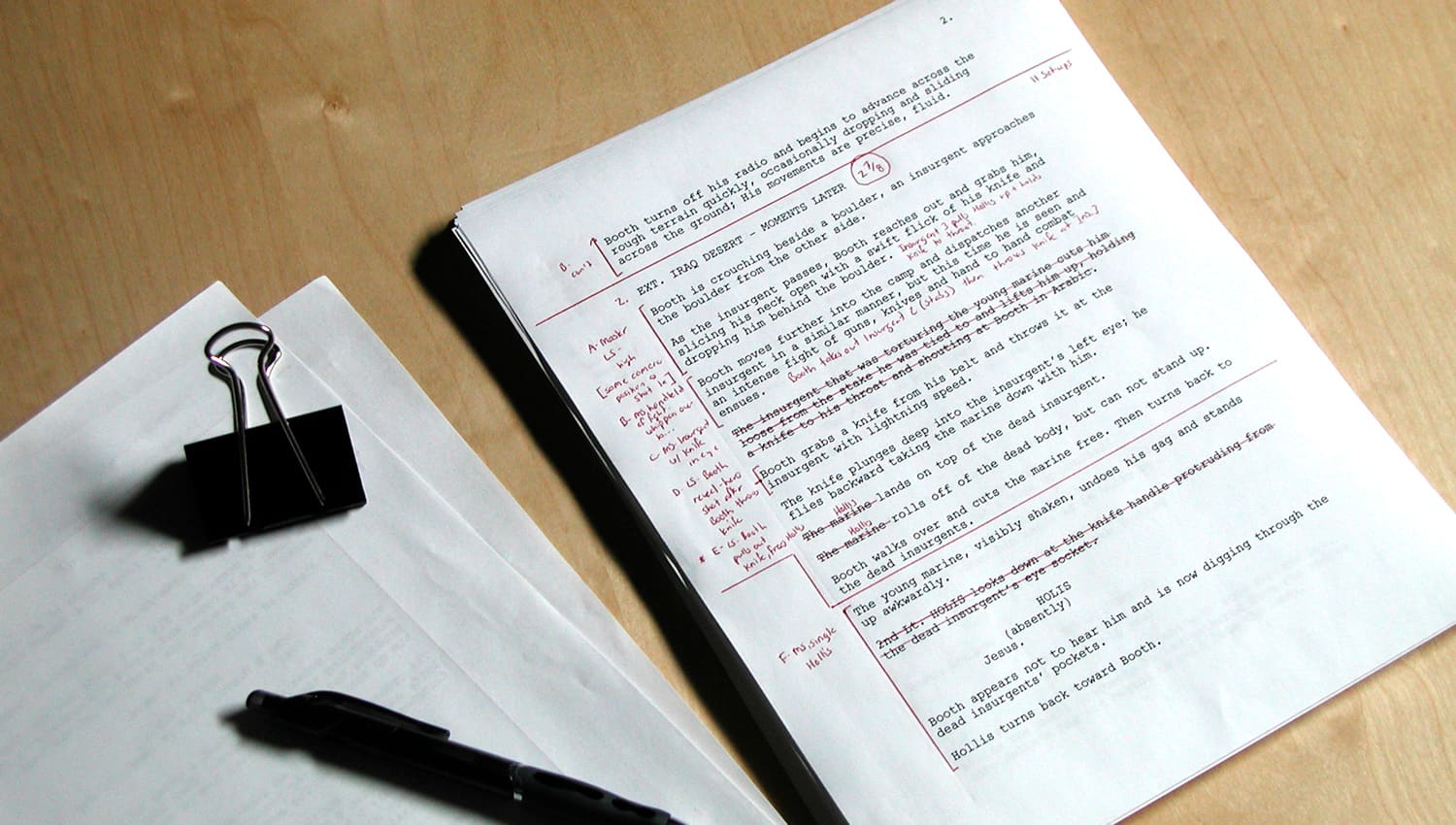

Prep is where the big part of the director’s job happens. That’s where we figure out: what is this scene really about, what is the story I’m telling, what is the emotional point of view of each character, and what is the intent and obstacle of each character? Now how do I illuminate that by how I shoot this scene? Where do the characters want to be physically in the set, and how do I demonstrate that with a camera? I cut it all together in my head before I shoot a single thing, so that my screen direction will be correct. And so that I can answer any questions that an actor might have about intention, or about obstacle, or about subtext, or about point of view. I have to know it all through and through and completely, know it cold. Once I know that, I can come on set that day and throw it all away, just like an actor does, and let the magic happen.

– Bethany Rooney, Critically Acclaimed Director, “Brothers and Sisters”, “Grey’s Anatomy”, “Desperate Housewives”, and “Private Practice”

Here are a few tips to get the most from your script before you start shooting:

- What is this scene about? Know the complete story arc of both the A-story and each subplot. Work through how each scene moves the story forward and the narrative purpose of each scene. Determine what each character wants in each scene, where each character is going, and where each character is coming from before the scene begins.

- How does it fit into the scene that came before and the scene that comes next? Determining this will help you design transitions to segue from one scene into the next scene. Let the emotion, energy, and pacing of each scene guide these transitions.

- What is each character’s motivation in this scene? Perform a character analysis for each and every scene. You can learn more about this process in the chapter, “Analyzing Character.”

- What is the driving subtext of each line of dialog? Invariably, actors will ask you why their characters are saying a particular line, so be clear what each character really means, and why he or she is covering this truthful subtext with the written line.

- What does each character really want and is he/she speaking the truth or masking it? While dialogue can seem to be a truthful representation of how a character feels, it probably isn’t. Look at the scene to determine why the character is masking or revealing his true intentions.

- How would you like the lighting and cinematography to serve the theme? In addition to the performance, determine how the other creative elements of filmmaking will work to enhance the emotion of each scene. From the blocking of the camera to sound design, understanding how the technique can adorn the actor’s performance can greatly enhance your control of the moment.

By unraveling and understanding these three principles in advance, you’ll be able to much more effectively tackle each scene on set.